The only thing I know about keeping livestock is…okay, I don’t know anything about keeping livestock. I mean, I know it’s hard work. I don’t know that from experience, since I’ve never kept livestock, but even sharing space with a pet (cats and dogs, certainly, and probably birds and lizards, what do I know?) means cleaning up after them. Even the tidiest of cats uses a litterbox and somebody has to deal with that.

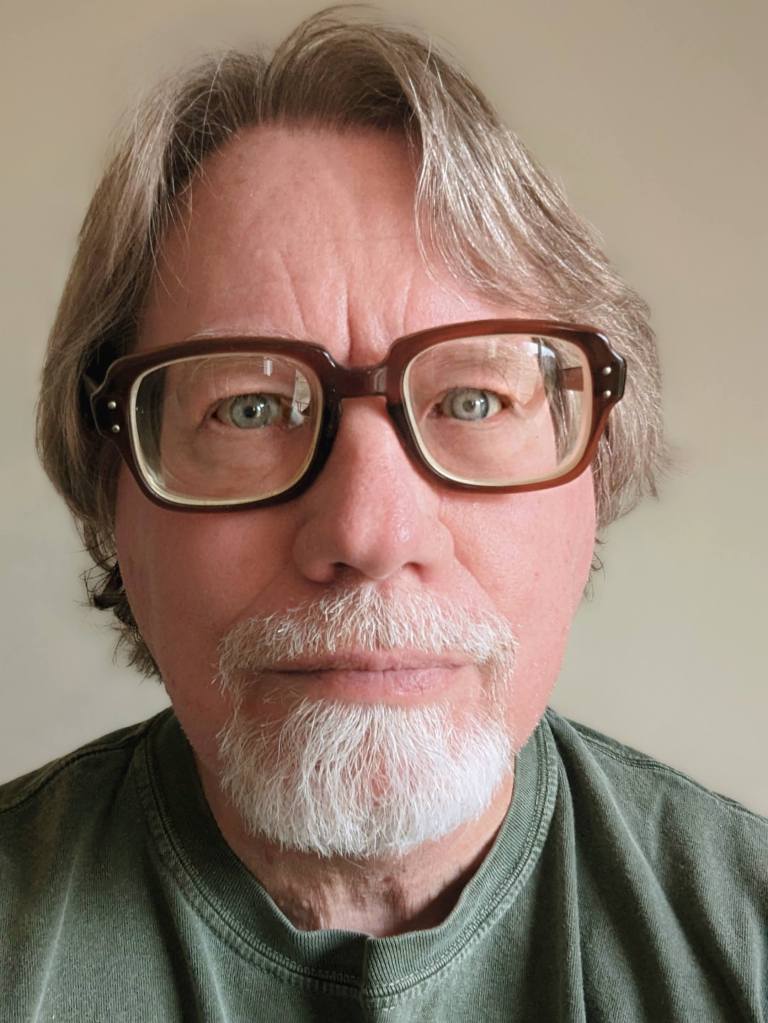

Why am I talking about this? Because looking over the photographs I took at the recent Iowa State Fair, I noticed I have a lot of photos of farm people cleaning stuff. Cleaning their animals, cleaning the gear needed to take care of their animals, cleaning the things their animals pull, cleaning up massive amounts of animal shit. Everywhere I went, men and women and kids were busy cleaning.

And when I say ‘cleaning their animals,’ I don’t mean they were just washing them (although there’s an astonishing amount of animal-washing going on all the time). I mean they’re shampooing them, blow-drying them, combing them, trimming them, vacuuming them.

Seriously, people were vacuuming off…something, I don’t know what. Loose hair? Dandruff? Barn grit? No idea, but everywhere you go in the animal barns at the fair, there are men and women and kids vacuuming their livestock.

These animals weren’t just being cleaned; they were being groomed. Meticulously groomed. (Okay, sorry, a slight tangent here. The term groom has a slightly hazy etymology. It’s probably(?) related to the Old English growan, meaning ‘to grow.’ At any rate, by the 14th century groom referred to a male servant who attended to officers (and their gear and horses) in a noble household. By the 19th century, the noun had been verbed, and groom referred to the process of tidying up or preparing for a purpose. So groom referred to both a person and what the person did. I don’t know why I thought you needed to know that, but there it is.)

As I was saying, these livestock animals (and I’m talking about cows, horses, pigs, goats, sheep, llamas, alpacas (is that the plural of ‘alpaca’?), rabbits, and chickens (do rabbits and chickens count as livestock? No idea.) are meticulously groomed. It’s clear that some of the grooming is done in the hope of winning a prize, but it was also clear that much of it was done out of pride and affection. That was especially true of the younger people.

Here’s a thing you probably need to understand. All this cleaning and grooming? It’s taking place in and around massive cooperative barns housing hundreds of animals. Animals are noisy, so these barns are a constant barrage of animal noises. Also? Animals shit and piss a lot. I mean, a LOT. And they’re not particular about where or when they do it. So even though there’s a constant stream (so to speak) of people shoveling, sweeping up, and carting of waste products (the logistics of livestock waste management must be staggering), the fact remains that these massive barns…well, they smell like you’d think they’d smell, but not as bad as you’d expect.

What I’m trying to say here is that there’s an astonishing amount of hard work done by the farm families who bring their livestock to the fair, and all that work makes the environment as pleasant as possible. One of my reasons for visiting the animal barns during the State Fair is to look at animals, of course, but it’s also to see this remarkable group of people cobble together a shared sense of community. There’s something very tribal about it. And as a sociologist by training, it’s fascinating.

But here’s the problem with being a sociologist: I know that the farming community I see at the State Fair is, largely, a myth. Around 40% of farms in Iowa are owned by corporations. Modern farming, even among non-corporate farms, is a business more than a self-sufficient way of life. The farming life we witness at the State Fair is something of a sentimental homage to an idea of rural living from the past. An homage grounded in nostalgia and an agrarian myth.

But so what? I’d argue there’s value in that. The fact is, it’s not corporations who are grooming their livestock at the State Fair. It’s not corporations who are hauling manure and polishing wagon wheels. It’s families doing that.

My visits to the State Fair animal barns always leave me impressed (and yes, a wee bit stunned by the smell and noise). I leave those barns profoundly grateful there are people–families–still willing to do the hard work of making sure the world gets fed. As myths go, this is a pretty damned good one, and I’m glad folks are keeping it alive.