Here’s a thing I’m going to do. Well, it’s a thing I’m thinking I might do. I’m not going to commit to actually doing it because it might be awful–for me and for any poor bastard reading this blog. Anyway, here’s the thing:

I’m thinking I might periodically look at one of my old photos and review or analyze it as if it were shot by a stranger.

I almost never look at my old photos. The very idea of looking at my old photos sounds boring as fuck. The idea of talking about one of my own photos sounds pretentious and annoying (and also boring as fuck). So why am I going to do this? I’ll explain the reasons later. Anyway, here’s the first photo I’ve chosen for this maybe-project.

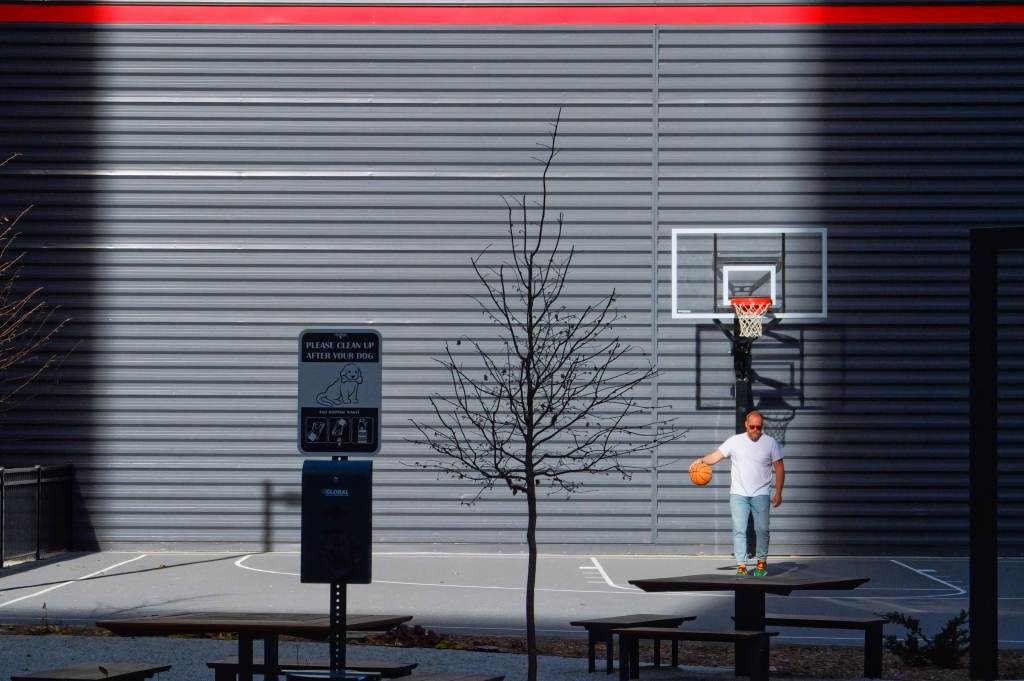

I shot this one late afternoon in September of 2006 (EXIF data is handy) with my very first digital camera, an Olympus C-770 UZ. A four megapixel powerhouse. It’s shot in a 4:3 aspect ratio, which I’ve never been comfortable with. As I recall, there was an option to shoot in 3:2, but it required some loss in resolution, which was noticeable in a 4mp camera.

I was having coffee with a friend and was somewhat distracted by the pattern of the late afternoon shadows. I recall shooting a couple frames of the shadows, but the images weren’t very interesting. At some point, my friend raised her arm to sip her coffee; the sun had shifted enough to illuminate the edge of the rolled up sleeve of her white shirt. I asked her to do it again and took the shot.

It’s not a great photograph, but that arm and sleeve humanizes the image. It’s not just a photo of some shadows; it’s a photo of a human moment. There’s a palpable mood here–quiet, reflective, casual, conversational. There’s something comfortably relaxed, intimate even, about that rolled up sleeve. I also like the fact that the image is intimate while being sort of impersonal; there’s almost nothing to identify the other person–age, gender, height, weight. It could be anybody. Fill in the blank.

Finally, the perspective puts the viewer IN the scene. Sitting relaxed across at a table with a friend in an almost empty coffee shop on a sunny afternoon.

Okay. Now, why am I talking about this 18-year-old photo? Here’s why.

I used to spend a lot of time thinking about photography. Thinking about different photographers, about styles and trends in photography, about the decision-making processes involved in making photos. For years I wrote a fairly regular series of essays about photographers (which can be found here). I started those essays primarily as a way to educate myself, but they became a tool for discussion in a Flickr group called Utata.

And then I stopped. I could probably cobble together some logical explanation for why I stopped, but really, who cares? The thing is, I just didn’t spend much time thinking about photography and photographers. I continued to shoot photographs, but lackadaisically and rarely with an actual camera. I was satisfied with my Pixel phone. Until a few months ago.

Again, I could probably cobble together some logical explanation for why I picked up a 12-year-old camera, but, again, who cares? I picked it up and started shooting with a camera again. Which led me to start shooting with another of my cameras. Which led me to decide to buy a new camera (which should arrive in a month or so). I’ll write about the new camera when it arrives. But the thing is, I’m thinking about photography again. I’m reading about photography again. And one of the articles I read included some bullshit about reviewing your old photographs.

Here’s a True Thing: I have no real interest in looking at my old photos. The very idea of looking at my old photos sounds boring as fuck. I mean, I shot those photos; I’ve already seen them. I’d rather look at new photos, photos shot by somebody else.

But this article suggested looking at your old photos as if they were made by a different person. The rationale is that we change over time, so our approach to photography probably changes. Which sorta kinda makes sense to me, since in a very real way I’m NOT the same person I was in, say, 2006.

So I said, “What the hell, why not?” and I opened up Google Photos and scrolled all the way down to the oldest photos. The photo above was one of them. It seemed like a good place to start.

I don’t know if this is a good idea or not. I’m not sure I’ll follow through on it. But back in the days when I was actively thinking about photography, I stumbled across some thoughts by Alfred Stieglitz and William Gedney about practicing in public. Although they didn’t put it quite like this, those guys were suggesting that if you’re serious about photography, you’ve got to be willing show your whole ass. Maybe this is related to that whole notion.