Let me first say this: I enjoy the hell out of my wee Ricoh GR3X camera. I’ve owned and used lots of cameras over the years, but I’ve never had one that suits my approach to photography so perfectly. I love that I can quickly shift between full manual control (which is a slower process but gives me control over every aspect of the exposure) and a setting that allows me choose the aperture I want and let the camera handle the rest (which is quicker and far more useful for street photography).

Last Friday I took a walk and decided to try something new. For the first hour or so, I’d shoot entirely in monochrome using the street settings AND I wouldn’t chimp the results. (For non-photographers, ‘chimping’ is reviewing the photos you just shot, which can inspire you to go “Ooh ooh” like a chimpanzee.) The second half of the walk, I’d shoot normally.

This where I fucked up. I somehow managed to change the street settings so the camera’s ISO was set to a minimum of 6400. What does that mean? ISO refers to the standardized scale that measures the sensitivity of a digital camera’s sensor to light. All you really need to know is this: the higher the ISO, the more ‘noise’ you see in the final image. In daytime, standard ISO settings are usually between 100 to 400. I was noodling around with an ISO that was at least sixteen times higher than normal. The result? Images like this:

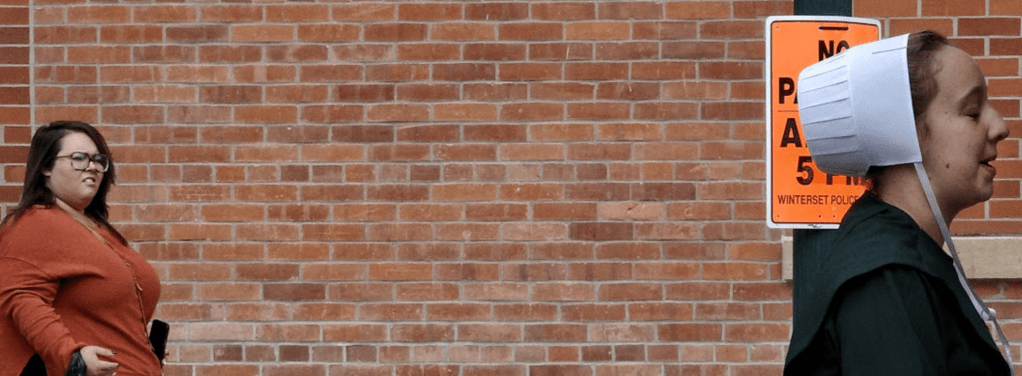

As you can see, noisy. But because I was refusing to chimp, I was unaware of the problem. So for an hour or so, I kept wandering, kept looking at stuff, kept shooting at the wrong ISO. When I saw a pair of workmen–one prone on the sidewalk with his head inside a manhole, the other feeding some sort of conduit tubing into the hole–laboring with the golden dome of the State Capitol Building behind them, I paused long enough to shoot a photo. I was confident I composed a decent shot, and the camera did its best to find a correct exposure based on the settings…but yeah, noise.

The thing is, I’ve learned to trust the camera. I’ve learned it’s incredibly responsive, that (assuming I’ve set it up properly) it allows me to shoot quickly, reflexively, on impulse. For example, I saw this tattooed guy in a tee shirt, toting bags of groceries, and wearing a ski mask. He was at a crosswalk, waiting for the traffic light to turn (or for the traffic to ease up enough for him to jaywalk). There was no time to properly compose a shot, but with the Ricoh all I had to do was react. I simply raised the camera in his direction and pressed the shutter button. Easy peasy, lemon squeezy. Except, of course, for that ISO of 6400.

Noisy. Harsh. But I can’t blame the camera. I’m the one who fucked up. I’m not saying these photograph would have been great if I hadn’t fucked up, but they’d have been…well, better.

And that’s okay. Making mistakes is human, right? And I’m an avid believer in what Alfred Stieglitz called ‘practicing in public.’ He wrote,

“Some people go on the assumption that if a thing is not a hundred percent perfect it should not be given to the world… Either you feel that a thing must be perfect before you present it to the public, or you are willing to let it go out even knowing that it is not perfect, because you are striving for something even beyond what you have achieved.

I wouldn’t claim these photographs are ‘given to the world.’ More like inflicted on the world. But yeah, I’m surely ‘striving for something beyond what I’ve achieved.’ Because what I’ve achieved here is that I fucked up. I suspect I’ll continue to fuck up on (I hope) an irregular basis.

Despite fucking up, I still had a good time. I not only believe in practicing in public, I also believe any walk on a sunny day is a good walk. And I believe in the reality of the Happy Accident, of which I have some evidence: I actually rather like the final ISO-fucked photo, which happens to be a selfie.