I should begin by saying I was never passionate about academia. In fact, I had no interest at all in academia. I almost became an accidental academic.

The only reason I went to graduate school was because I was badly burnt out after five years working in the Psych/Security unit of a prison for women and seven years as a criminal defense private investigator. I wanted a break. Hell, I needed a break. As a working class guy, I had no idea that you could actually get paid to attend graduate school. When I learned that, I applied to half a dozen different universities in half a dozen different disciplines. American University offered me the best deal: free tuition AND a small stipend to study Criminal Justice. So that’s what I did.

That was my plan. Take a year or two off, loafing as a graduate student, then find something else interesting to do. But as I was finishing my MS in Justice, I was offered more money to go for a Ph.D. So, again, that’s what I did.

A couple of years later I found myself with a contract from Fordham University to teach Sociology. I loved teaching and I was good at it. But I disliked academic politics, and I positively hated academic writing. Still, it was relatively easy work, so I didn’t complain. Then one day I was sitting in my Lincoln Center office reading an old paperback book I’d picked up at some second-hand bookshop and the Chair of the Department wandered in. He asked what I was reading.

Here’s a true thing about academia: it’s about specialization. For example, you can’t just study history. You have to study English history. But not just English history, English history of the Tudor period. But not just Tudor history, but Tudor history during the reign of Henry VII. And not just the history of Henry VII, but the fiscal policies of Henry VII. Academia is about narrowing your interests until you become a specialist in a small segment of a larger field of learning.

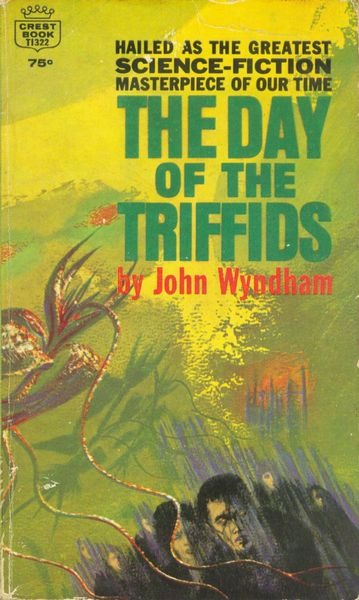

As a larval academic, I was expected to decide on an area of specialization and spend my time concentrating on it. I was expected to study the appropriate academic journals. Instead, I was reading a 1951 science fiction novel about venomous, carnivorous plants capable of locomotion (that’s right…walking plants) and the collapse of society.

“Are you reading this for your classwork?” I was asked.

I could have said yes. I mean, I could easily argue that the story examined economic systems (these dangerous plants, triffids, were cultivated as a source of industrial quality oil). I could say in all honesty that the collapse of society (a strange ‘meteor’ shower had turned most of the world blind, leaving only a small segment of the population capable of sight) resulted in a variety of localized ad-hoc systems of governance and justice, which could be explored through various criminological theories. I could accurately claim there was value in studying how a 1951 novel explored the ways new social norms and mores were formed from the bones of the old system. I could have absolutely justified reading The Day of the Triffids.

But the truth is, it never occurred to me that I needed to justify it. I told him the truth; I was reading for the pleasure of it. I was actually surprised by the disapproving, judgmental look on his face. I was even more surprised when I discovered the university had advertised a tenure-track position in the Sociology Department, and I hadn’t been asked to apply. I applied anyway, but I wasn’t even offered an interview, despite the fact that my teaching evaluations were among the highest in the department.

There were probably other reasons I wasn’t considered for the position. There’s often an unspoken (and sometimes loudly spoken) bias by academic theorists against practitioners. Some academics assumed my years as a private detective and as a prison counselor tainted my views. There’s a saying: In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is. But after my brief encounter with the department Chair over Triffids, there was an obvious shift in attitude.

You could say triffids killed my academic career. It’s probably more accurate to say triffids saved me from an academic career.

In the 24 years since I finished my master’s degree in mathematics, there has been a strong desire to pursue a Ph.D. in the subject. A number of circumstances prevented that, not the least of which was the expense of guiding 4 young humans to adulthood. The biggest impediment, though, was that the only university within driving distance that offered a Ph.D. in mathematics only offered the degree studying mathematics in education.

It may sound strange for someone who dedicated his life to teaching mathematics that I have absolutely no desire to study mathematics teaching. I could have studied what technique is best for teaching students how the movement of game pieces on a Monopoly board inform us of the laws of probability. However, by then, I had already found that the best way to teach mathematics to a group of people with different experiences is to get to know the kids, connect with them, make them feel important. You do that and you can teach them anything.

I still want that Ph.D. in mathematics, even though the remaining time in my teaching career is measured in months instead of years. But if I am going to do it, I want the time spent to be important to my interests.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Teaching is wonderful and can be incredibly fulfilling IF you have good students. As a Ph.D. student, I taught at American University in DC. My students tended to be privileged kids, most of whom were fine, but far too many thought their privilege should extend to getting good grades without doing the work. I had to deal with lot of parents in diplomatic corps demanding to know why their child didn’t get a good grade.

When I taught at Fordham in NYC, a LOT of my students were first gen college kids. They WANTED to learn, and they were an absolute treat to work with.

I had the same experience teaching with the Gotham Writers Workshop–motivated students, mostly adults.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No doubt, students make the difference.

LikeLike

At a small liberal arts college in the 70s I was inspired by the professors who would explain tangential connections to the subject at hand with breathless excitement to reinforce the importance of this information in the well of life, or just because it was a cool fact they’d picked up somewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. Somebody (can’t recall who) told me there were two basic approaches to teaching. One was filling the bucket–giving the information necessary to understand the subject. The other was lighting a fire–getting people engaged in the subject. They’re both necessary, but the latter is far more fun than the former.

LikeLike