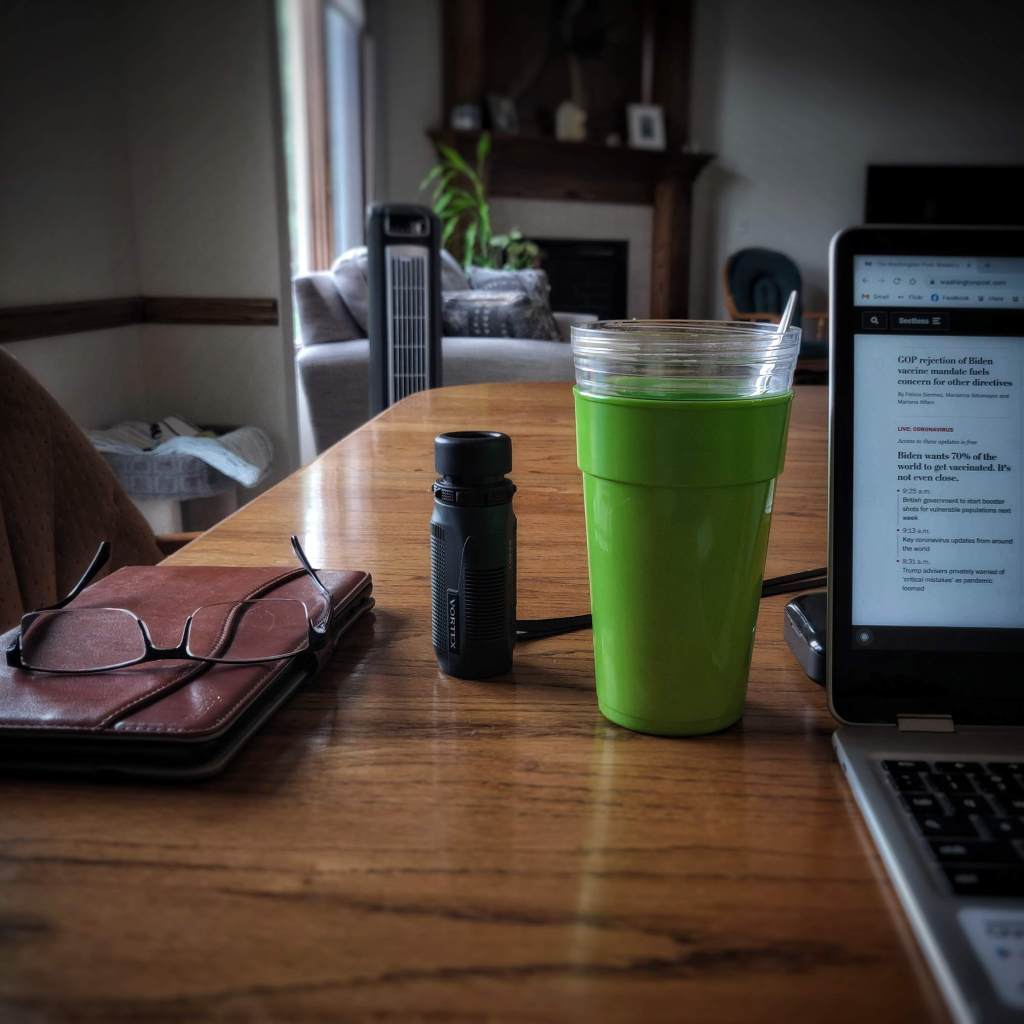

From some indeterminate point in May to an equally vague point in September, I drink cold brew coffee in the morning. I drink it from a lime green plastic glass — because something about that color appeals to me in a summer sort of way, and because I like the clicky sound made by the iced tea spoon when I stir it. In September — at the end of this week, in fact — I’ll shift back to hot coffee, which I drink in a brown metal insulated mug.

I could, of course, drink the coffee in any sort of container and it would taste as good, but I choose those two because they please me. They’re a part of my morning ritual. Greet the cat, check the perimeter (with the cat, of course), feed the cat, get my coffee, read the news. I live a fairly irregular and unscheduled life, so that morning ritual provides a sort of ground-level continuity — a semi-stable foundation to begin the day.

What does that have to do with digital books? Nothing, in a material way — but they’re related in a sort of philosophical way. Recently a friend mentioned they couldn’t bring themselves to buy an e-book reader, and asked me how I could bring myself to abandon physical books. This is my answer.

A lot of people have a relationship with books that’s similar to my relationship with my lime green plastic glass. The thing is, physical objects can develop a certain presence that stems from the object’s personal history with the user. We’ve all experienced this. Maybe you have a favorite shirt — something faded and worn and not suitable to wear in public, but imbued with memories and a weird sort of affection that makes it impossible to discard. Maybe you have a screwdriver or soup ladle inherited from a grandparent, or a some old work gloves loaned to you by a friend who moved away before you could return them, or an early Baywatch poster that’s sort of embarrassing now but still un-throw-awayable — something (some thing) that has a personal meaning to you and only you.

So, how could I abandon physical books? How could I give up that tactile experience of holding a book in my hand? How could I shift away from the sound and feel of turning a physical page? Didn’t I miss the particular smell of a book? How could I reduce a great novel to nothing more than a collection of digitized ones and zeros?

I get that notion. I totally do. There are absolutely some physical experiences that clearly lose something important when they’re de-objectified, when objects are turned into information. The ringing of a church-bell, for example; we can digitally reproduce that sound, but we can’t reproduce the experience, the physicality of a ringing bell, the way the sound waves impact our bodies.

But for me, the impact of a book — and especially of a novel — isn’t in the substance of the paper and the binding, it’s in the ideas generated by the story. It’s in the unique and intensely personal interpretation of what’s written. For me, it’s the writing that matters more than the way it’s presented; it doesn’t matter to me if the words are printed on a physical page or digitally reproduced on a screen.

Originally, I thought it would matter. In fact, I refused to buy an e-book reader because I was concerned it would degrade the experience of reading. But then, back in 2010, I was given a Nook, an e-reader developed by and for Barnes & Noble booksellers. It came with a couple of classic novels already loaded — both of which I’d read and re-read several times. Pride and Prejudice and The Three Musketeers. Because it was a gift, I felt obligated to at least try using the Nook. So I started to re-read the story of Charles de Batz de Castelmore d’Artagnan and his ridiculous quest to become a musketeer — and by the time I finished the third paragraph, I was caught up in the narrative.

Imagine to yourself a Don Quixote of eighteen; a Don Quixote without his corselet, without his coat of mail, without his cuisses; a Don Quixote clothed in a woolen doublet, the blue color of which had faded into a nameless shade between lees of wine and a heavenly azure; face long and brown; high cheek bones, a sign of sagacity; the maxillary muscles enormously developed, an infallible sign by which a Gascon may always be detected, even without his cap—and our young man wore a cap set off with a sort of feather; the eye open and intelligent; the nose hooked, but finely chiseled. Too big for a youth, too small for a grown man, an experienced eye might have taken him for a farmer’s son upon a journey had it not been for the long sword which, dangling from a leather baldric, hit against the calves of its owner as he walked, and against the rough side of his steed when he was on horseback.

That pair of sentences would make any modern editor have a seizure, but they set the tone for this particular novel. More importantly, they create an image in my mind of the character d’Artagnan. Reading it digitized — like it is here — creates the same image in my mind as reading it on a printed page. That mental image has nothing to do with the medium that created it, paper or digital. It’s unique to me; your mental image of young d’Artagnan is probably different, because…well, fuck. I have to go off on a tangent here. I’ve been trying to reduce the number of tangents in these blog posts, but damn it, here we go.

I think we can all agree that with very few exceptions, books are better than the movies made from those books. One reason for that is because the characters in movies rarely resemble the characters we create in our mind when we read a novel. But on occasion, a character is so perfectly cast that we impose that actor’s face on the character in the novel. And the 1973 film adaptation directed by Richard Lester has permanently imprinted the face of Michael York on my personal interpretation of d’Artagnan. Now and for the rest of my life, when I read The Three Musketeers, I see Michael York.

Right, tangent over, and back to my point, which is as follows: some physical objects, though routine contact with people, develop an almost mystical connection to the person who possesses them. I have a relationship with my lime green glass, for example. My cold brew coffee would taste as good in a ceramic mug, but the glass means something to me. But my relationship with books, and particularly novels, is different. That relationship is grounded in the ideas created through the writing, not in the device that contains them.

When it comes to books, my interest is in the cold brew, not the lime green plastic glass.

I had a similar conversation today when someone asked what I was currently reading. I replied, “I am reading ‘Kane and Abel’ at home, I’m listening to ‘Paradise Lost’ when driving along, I have ‘That Way Madness Lies’ on my Kindle for when reading in a doctor’s waiting room, and I am reading a Cyborg graphic novel in the school library when I get the time.”

My friend responded that I am only “reading” one book. The others don’t count. What followed was a discussion on who gets to decide what I count as reading.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I used to keep company with a woman who enjoyed reading aloud. We’d take turns reading chapters of novels to each other. It would be ridiculous to claim I’d only ‘read’ half of those novels.

It’s also useful to consider the etymology of the verb ‘read’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hm, I think you friend is not a multitasker. True readers for pleasure do what you are doing all the time. (Although I shudder at Paradise Lost. I had to study that for A Level English and hated it. There are not full stops or any punctuation. You just can’t stop once you start. It was torture to my 17-18 year old self. It was also winter and I could not work on it with Mum wittering on in the background so had to work on it in my freezing cold unheated bedroom. I recall being sat in a coat and gloves.)

I just checked. I have 2 (very different styles) novels in paperback on my table. A hardback political book and my Kindle with a book about hypothyroidism on it (I suffer this). I also have another book about hypothyroidism that I’m reading in paperback. I have Michelle Obamas’s book Becoming on the go on Audible and a factual book on my phone. I’m “reading” all of them. I’ve physically read from 2 of them so far today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another advantage of ebooks is that ereaders are lighter than hardcover books, which is important if (like me) you like to begin a nap by reading. If I fall asleep with an ebook, I’m less likely to be injured by a heavy book on the nose.

LikeLike

I will always read Tolkien out of a printed book. Anything else is up for grabs.

That’s odd isn’t it? I do plenty of digital reading, and get plenty of enjoyment from it. My brain doesn’t know the difference. With JRRT it’s a certain amount of reverence for the text I suppose.

Do you have a “holy book” that you would never replace with a digital copy?

C

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is it odd? Sure. But it absolutely makes sense.

Your choice of term — reverence — is perfect. Reverence often requires a behavior to be enhanced by an additional action — the way people bow their heads to pray, or rise when a judge enters the chamber, or raising a hand to swear an oath. Holding and reading from a physical copy of a book can be a casual act of reverence.

I don’t have any ‘holy’ book, unless you count books on art and photography. I don’t know if that’s because publishers tend not to make digital editions of photography books or if I’m just not confident that digitized versions would be as accurate in terms of color.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do have a book I would never read any other way than in the 1800’s printed hardback copy I found in an antiques market many years ago (actually I bought a set of about 10 of the same printed edition of Dickens’ works). It’s A Christmas Carol.

The paper is perfect, the speckling with age in place, the lovely sketches and the faded red cloth hard cover are part of the experience. I tend to read it in the run up to Christmas around every 2 years or so. I’m 3 years out this year, so it’s highly likely I’ll read it this December.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds holy enough to me. Enjoy your ritual!

Cheers,

C

LikeLike

I’m curious…does your mental image of that “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner” look like Alistair Sim, who starred in the 1951 film version of A Christmas Carol? Or another actor? Or is your Ebenezer Scrooge unique to you?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I tried to reply to this question last night, but the reply seemed to vanish. I will try again.

I first read A Christmas Carol when I was around 12 or 13. I found an old copy of it, with a red cloth cover, in the sideboard behind Mum’s sewing box. I think Dad probably bought it from a charity shop because I’d not seen it before. I opened the cover and started to read and it gripped me immediately. I just sat there on the floor in front of the open sideboard cupboard and read. Quite some time later Mum found me there still. I loved the story but I also loved the old fashioned language of it and how poetic it can read. I had never seen a film of it so all the characters were my own.

I still have never seen a film of it. I have been in it at a small theatre group (where I met David) many years ago now and I stage managed a much bigger production of it at a proper theatre I was involved with. That production had a wonderful old actor playing Scrooge. He was perfect in looks, gait and voice. Trouble is he was really deaf and prone to forgetting his lines/missing his queues. There was no way he could hear the prompt or me shouting from the wings so the cast devised ways to pass in front, behind, to the side of him and try to give him his lines or a cue if he dried. It worked quite well, although he did occasionally walk off to my desk and ask! It was testament to his skills as an actor that the audience didn’t seem to care or even really notice. So these days if I have anyone in mind when I read it, it’s probably him. Eric F. Abbott

LikeLiked by 2 people

That is a perfectly Ebenezer face. A magnificent scowl–a bad-tempered blend of a glower and a glare. Perfect.

LikeLiked by 1 person