“I don’t believe in coincidences.” You’ve heard that line spoken in every detective show that’s ever been on television. It’s ridiculous, of course, because coincidences exist. I mean, that’s why we have a word for it.

For example, about a week ago I was shooting a photograph of some yellow bollards at the very back of a massive and nearly empty parking area of a big box store. I was using an old Polaroid Spectra 2 camera, trying to get a feel for what the camera could do, using Impossible Project color film, trying to get a feel for what the film could do. In other words, I was experimenting.

Before I took the shot, however, a car pulled up and the driver rolled down his window. He was an old guy (and as I say that I realize he was probably around my age — maybe even a bit younger), and he grinned at me and my Polaroid camera and asked “How do you use your camera?”

I’d had a similar question from a police officer a couple of weeks earlier (there’s a coincidence for you — and coincidentally, one of the photos I shot before the arrival of the police officer was of a yellow bollard). With that encounter in mind I launched into an explanation of how I used the camera as a descriptive tool, a device designed to record a small but precise rectangle of the reality in front of the lens. I was prepared to elaborate on that idea — to spell out how the decisions of what to include in the frame and what to exclude from the frame were expressive decisions, and so even if the final image seemed mundane — like, say, a group of yellow bollards — there were still aesthetic aspects to be considered, as well as the notion that mundane objects and structures can be interpreted as a manifestation of humanness. In other words, my decision of what to include in the frame is, in part, a reflection of some other person’s past decision to…

“No,” the old guy interrupted. He said, “No, I mean, the camera. The camera. How do you use that camera? I thought they stopped making Polaroid film.” So I told him about the Impossible Project. Then I shot the photo.

That photo, coincidentally, sparked a brief discussion on Facebook because apparently relatively few people were aware those posts are called bollards. And coincidentally, this morning on Facebook I learned that William Christenberry had died.

Just over a decade ago I admitted that although I’d been shooting photographs for years and I knew how to operate a camera, I was pretty ignorant about the history of the craft. I had only the barest notion of what had been done in photography in the past, or who had done it, or what they were thinking when they did it. So I decided to educate myself, and I decided to share my education with a group of friends in a Flickr group called Utata. I’d pick a photographer, do some research, write a short article based on the research, and we’d discuss it in the group. We called it the Sunday Salon.

One of the first photographers I picked for the Sunday Salon was William Christenberry. Why? Because I came across his name somewhere and liked it. I didn’t know anything about his photography, and when I began to look at his photographs, they didn’t make a lick of sense to me. I saw an old black-and while photo of a dilapidated juke joint somewhere in Alabama. Then I saw a photo of the same building, only this time it was in color. Then another photo of the same place, and another and another — all of the same building.

I began to get it. This guy wasn’t just photographing the building; he was photographing the history of the building. Christenberry wasn’t trying to make art — at least not at first. He was just creating a document, a description of how particular structures evolved and devolved. He went back to the same places year after year to record how things change.

A building may be static, but the world around it is dynamic. What happens in the world is reflecting by the changes to a building. Wind and rain have an effect, the settling of the structure into the soil has an effect. Paint fades, shutters have to be replaced, buildings begin to tilt. Humans very obviously have an effect; they do the painting, they replace the shutters, they repair the damage.

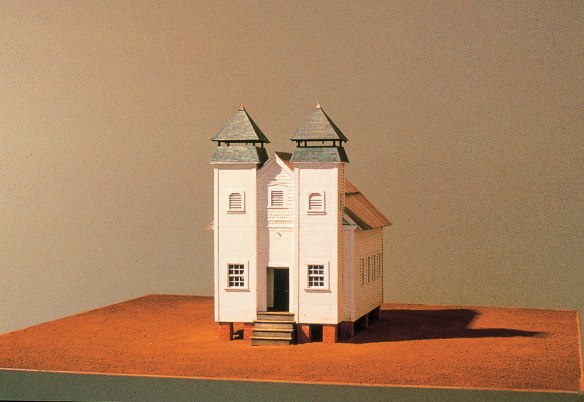

Over time, Christenberry’s simple documentation process became deliberate, thoughtful art. His first photographs were shot using an old Brownie camera given to him when he was young, but as the project progressed, so did his use of technology. He eventually began to shoot with a Deardorff 8×10 view camera. Christenberry even began to take measurements of some of the buildings and recreated them as sculptures.

“What I really feel very strongly about,” Christenberry once said, “and I hope reflects in all aspects of my work, is the human touch, the humanness of things, the positive and sometimes the negative and sometimes the sad.”

There it is. The humanness of things. Those half-dozen yellow bollards? Somebody deliberately put them there. Somebody designed the shape of that small area, somebody chose to plant a tree in the middle of it, somebody decided what type of tree to plant. Somebody designed that parking lot. The humanness of things is always there.

I believe in coincidence. I love coincidence. I enjoy the weird, improbable chain that links an encounter with the police to an old guy in a parking lot asking about an old camera to a discussion on the etymology of the term bollard to the work of William Christenberry to a photograph of yellow bollards. I believe in coincidence and I believe in the humanness of things, and wouldn’t the world be terribly dull and uninteresting without them.

Fascinating. I’d never heard of William Christenberry – is it wrong to admit I hadn’t read your Sunday Salon?

LikeLike

Thank you for letting me know about the Impossible Project. I think I have an old Polaroid sitting around, and this might be a reason to pull it out.

LikeLike

It’s fussy film, and using old cameras is risky — but when it all works (or even sort of works) it’s very cool. If you try it, let me know.

LikeLiked by 1 person