Well, we did it. Last night Iowa did democracy. Okay, yes, the Iowa caucus is an antiquated, massively inconvenient, perversely idiosyncratic political system. In action, it feels almost tribal — like we’re only a few steps away from folks in animal skins, squatting around a fire, raising their hands and grunting to signify approval or disapproval.

We’re talking basic, precinct-level democracy here, folks. Even the concept of a precinct is old-fashioned. The term comes from the Medieval Latin precinctum, which referred to an enclosure or boundary line. Precinctum itself is the joining of the prefix prae– (meaning ‘before’) and cinqulum — a girdle or swordbelt. How cool is that?

In modern electoral terms, a precinct is a predetermined boundary creating the smallest geographical unit used for tallying election results. In Iowa, we have 1681 voting precincts. Rural precincts can be pretty big, but in the cities they’re often composed of just one or two neighborhoods. They’re personal. You attend a caucus with your neighbors — the people you most often see out shoveling their sidewalks or buying beer at the market. The caucuses are personal and they’re public; there is no secret ballot in a Democratic party caucus. Everybody there sees who you support.

Here’s another thing: each of those 1681 precincts hold two caucuses; one for Democrats and one for Republicans. That’s 3,362 separate caucuses. And they’re run by volunteers. Each party in each precinct has an unpaid precinct captain and a handful of volunteer precinct workers.

I live in a fairly middle class, fairly white, fairly dull suburb of Des Moines. There’s about 2,500 people in my precinct. Last night around twelve percent of them showed up at the Democratic caucus. That may not sounds like much, but a caucus has a lot going against it. It’s a time-consuming gig, it’s held on a Monday night, they don’t serve alcohol, and this year it was held during a blizzard warning (happily, the blizzard slowed down and didn’t hit until this morning). So 12% is a good turnout for a caucus.

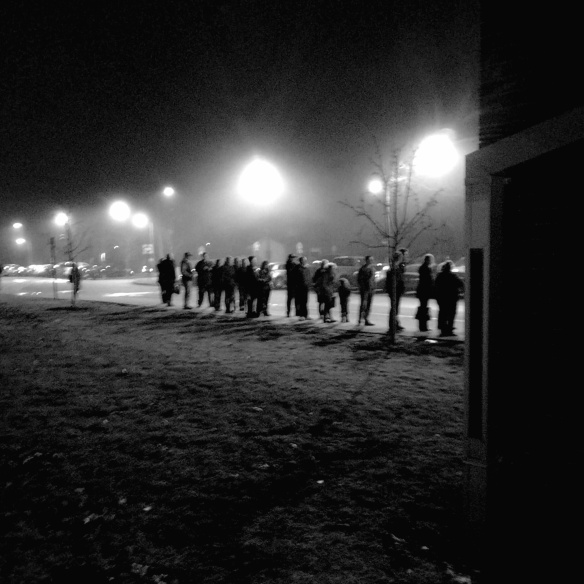

The Democratic caucus was held in the cafeteria of a local elementary school; the Republican caucus was held at a Baptist church — read what you want into that. People were already lined up when I arrived (got there around 6:30, half an hour before the caucus was scheduled to begin). Even before I got inside the school doors, the line snaked out down the sidewalk and around the corner.

It was a nice, orderly line — until you get through the cafeteria doors. That’s where the madness begins. It’s pretty simple if you’re already registered to vote as a Democrat. You just sign in and go find the cookies and brownies. But those poor bastards who 1) have recently moved and aren’t registered in that precinct, 2) or haven’t registered to vote at all, 3) or were registered as a Republican but want to switch to Democrat, they all have to fill out paperwork while the rest of us went to work on the snacks.

Once that fuss was dealt with, we had to elect a permanent caucus chair. That thing I mentioned earlier? You know, about this thing being run by volunteers? This is a perfect example. The precinct captain who has gotten everybody in the cafeteria and made sure they’re all registered, he (in my precinct it was a guy), his first order of business is to ask if anybody else wants his job. He’s just the temporary chair, and the caucus needs to elect a permanent precinct chair to oversee the caucus.

Seriously. At that point anybody who’s in the room can stand up and try to convince the people there to cede all control to him. In my precinct (and in probably ever other precinct) everybody pretty much agreed they didn’t want to deal with that, so the temporary chair was approved to become the permanent chair.

Then we had to count ourselves. I know. You’d think maybe they’d just count the names of the folks who’d signed in on the voter rolls, but no — we had to do an old school hand count. Literally. It began in one corner of the room; everybody had to raise their hand, one at a time, and count off. “One.” “Two.” “Three.” And so on. It sounds stupid and inefficient, but it actually went smoothly.

There were three hundred and twelve of us. Old folks, a few young couples with infants in carriages, some middle-aged professionals, a smattering of working folks, a few college students, one old guy with a cane who was a proud Korean War veteran, some young adults for whom this was clearly their first presidential election. Probably 80% were white. I’m guessing the average age was probably somewhere in the mid-to-late 30s. It seemed pretty representative of the neighborhood.

Then we got down to the actual physical caucusing. And I mean physical. Everybody had to actually stand up (which was sort of a relief after sitting so long at cafeteria tables designed for elementary school children) and move to a designated spot. Hillary folks to that corner, Bernie folks to another, O’Malley folks to a third corner. This was the first test of the evening. A candidate has to have the support of at least 15% of the caucus goers in order to be considered a viable candidate. O’Malley had maybe eight supporters. Not nearly enough.

The chair designated thirty minutes for folks to persuade the O’Malley people to stand with another candidate. It took about five. Most of his supporters went to the Hillary corner. I’m not saying the fact that the Hillary folks had provided the best snacks influenced that decision, but the muffins disappeared pretty quickly at that point. We were supposed to use the rest of the half hour to try to persuade folks who supported a different candidate to shift their alliance, but it was really clear that nobody was interested in switching.

At that point we counted ourselves again, this time according to candidate preference. It was the same process. You count off and raise your hand. The Hillary folks counted off first. Two hundred and thirty-four. Bernie could only muster seventy-eight. It didn’t matter that much though, since the Democratic is all about determining the number of delegates to the statewide convention. In the end, my precinct will send five delegates for Hillary and three for Bernie.

Overall, as you probably know, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders ended the caucus in a statistical tie. The New York Times has published a map showing the results from each individual precinct. It shows broad support for both candidates in urban, suburban, and rural precincts. It’s really a pretty remarkable result — more encouraging for Bernie than for Hillary, I think, but demonstrating that Democrats have a pair of strong candidates. I also hope that map suggests that whichever candidate wins the nomination will have the support of the entire Democratic party.

For me personally, this was the coolest thing about last night’s caucus. After the final count, everybody applauded. Everybody. Hillary folks, Bernie folks, disenfranchised O’Malley folks — we all stood up and spontaneously applauded. Nobody was angry, nobody felt excluded, nobody pouted. And best of all, during the actual caucusing nobody had attacked or insulted or denigrated the other candidate. As we walked out of the little cafeteria, everybody seemed cheerful and hopeful.

We’d done democracy, and it felt good.

And so the flickering candle of hope burns a little brighter…. Thank f*** there’s an antidote to Trump ;-)

LikeLike

I’m really not worried about Trump. There’s no way he can be elected, even in the unlikely event he gets the GOP nomination. The numbers just aren’t there.

LikeLike

I saw that in our news yesterday. I see he’s throwing a hissy fit because he lost :-D

LikeLike

thanks for a great inside view!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now, that was more interesting than all the descriptions of a caucus I have seen in the last weeks. We have a lot of press covering of your election over here this time.

LikeLike

It’s a terribly inefficient process, and that discourages participation. But the people who DO participate are usually more knowledgeable and more passionate than the average citizen. So maybe it balances out.

LikeLike

this reads very… civil. maybe as you say, two strong candidates, and with some distinction among them, but not of the fragmentation found elsewhere. yes, where elsewhere is just one more party.

however, my greatest concern was:

«Nobody was angry, nobody felt excluded, nobody pouted. »

not sure if it can all relate to the process, but it may indicate that the muffins were “ok”. if they were really good, then there would have been some pouting. if they were really, really good, then there may have been some anger. alas, the disenfranchised/exclusion were just about O’Malley and muffin-deprived voters. I am going to imagine that O’Malley + muffin-deprived > 15%, and the resulting delegate count would have caused a winner in the overall count — you know, because of the butterfly-muffin effect.

LikeLiked by 1 person