There was a great deal of fuss yesterday about the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. And rightly so; it’s beautifully written — simple, eloquent, thoughtful. In fact, it’s hard these days to appreciate just how thoughtful it was.

That’s partly because we tend to think of it as a ‘speech’ — as an act of public oratory. A stirring and moving speech, to be sure, but basically we tend to see it just a speech given to an audience to dedicate a cemetery.

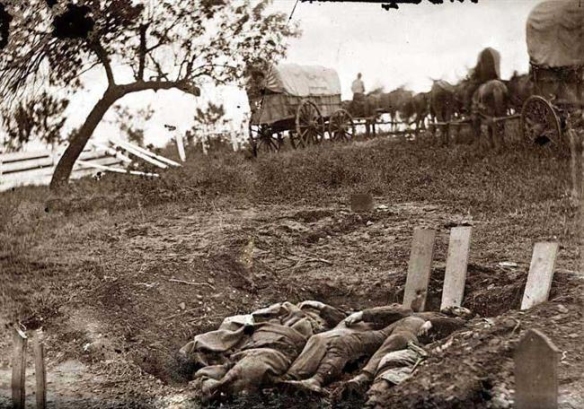

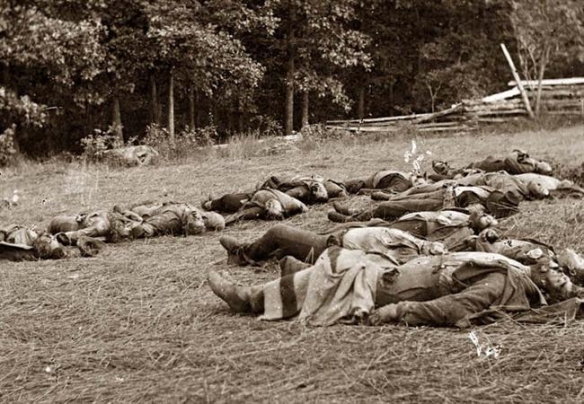

A cemetery. A burial ground. A graveyard. Yes, we all know the Gettysburg Address was to dedicate the ground on which the Battle of Gettysburg was fought. For us, that’s history. For Lincoln, it was a recent event. The dedication took place only four months after the horrific three-day battle. Nearly eight thousand men were killed. Nearly thirty thousand were wounded or went missing (‘missing’ might mean the men ran away; it might mean they were simply obliterated). Many of the wounded were still convalescing in Gettysburg when Lincoln gave his short remarks. Coffins were still stacked at the railway station where he arrived.

The battle had been so savage and so many people had died that almost immediately afterwards it was clear that something astonishing and awful (and I mean awful in the oldest sense of the term) had taken place at Gettysburg. Something so appalling that it was necessary for the entire nation to pause a moment and recognize it.

Why did Lincoln wait four months to dedicate the battleground? Because it took that long to gather the dead, try to identify them, and rebury them. That’s right, rebury them. We forget that the battle took place in the first week of July. Try to imagine eight thousand human bodies (many of which were dismembered) scattered over several hundred acres. Imagine five thousand dead mules and horses. Imagine the July heat, and the stench of decomposition. The noise of bluebottle flies was said to be deafening.

Now try to imagine the task of cleaning all that up using Civil War-era technology. Picks, shovels, muscle. The horses were burned; the men mostly buried in quickly-dug shallow graves, many of which were later washed open by heavy rains that fell in the second week of July.

The grisly work was done by Union troops, by captured Confederate soldiers, and by unfortunate townsfolk who’d been dragooned by the authorities. The town of Gettysburg, at the time of the battle, only had a population of about 2500. Fewer than half the number of the dead.

In the four months between the battle and the dedication, the organizers bought the land on which the battle was fought, they laid out a design for where the graves would be dug, they re-interred most of those bodies, they telegraphed invitations and coordinated a public dedication (Lincoln, by the way, wasn’t the main speaker; his job was to present some brief closing remarks after the main speaker was finished).

To do all that in 120 days was a remarkable feat.

And don’t forget this: the war wasn’t over. The outcome was still very much in doubt. There’d never been anything on the North American continent remotely like the ongoing slaughter of that war. They were more than two years into the war, there were already nearly a quarter of a million casualties, and nobody could guess how much longer it would last. That’s what Lincoln faced when he went to Gettysburg. Read his speech with that in mind, and you’ll see he wasn’t just dedicating a national cemetery; he was telling the nation there was more to come, and asking them to maintain their resolve.

Lincoln spoke about the “unfinished work” and “the great task remaining before us.” He acknowledged the uncertainty of whether the nation “or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” Despite all that, he talked about the necessity of an “increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.”

To stand on the site where so much death and destruction had taken place, to tell the public there would be more of the same, and to ask the public to accept the necessity of sacrifice on that scale in order to maintain an ideal — that’s just astonishing. What’s even more astonishing is this: the people agreed to accept that burden. The war would stagger on for another year and a half after Gettysburg. Tens of thousands more would die. Lincoln himself would give the last full measure of devotion before the end.

Think about that. Then think about this: there are people in this nation today who talk of seceding from the Union because they dislike a health care policy. There are people in this nation today who talk about secession because they believe the president isn’t a Christian, or because they feel their taxes are too high, or that someday they might not be able to purchase high capacity ammunition magazines.

And those people consider themselves to be patriots.

Thank you. I admit I love these posts where your teacher and researcher and historian sides all come out together to form such a powerful message.

LikeLike

My ex once told me I had a talent for boring people in a multitude of subjects. I’ve been honing that talent ever since.

LikeLike

I have never been to Gettysburg, but I teared up at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington reading the address inscribed in its walls.

It is a sad irony that so many of these current-day kooks who talk of secession (as well as the right-wing clowns who clog Congress) claim Lincoln as their own.

LikeLike

Lincoln was really a remarkable speechwriter. “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” Dude could write.

LikeLike

Brilliant, fantastic writing. As usual. Being originally from Pennsylvania, I’ve yet to get to Gettysburg. But it’s a trip on my list when the kids get a little older. I’ve seen that first photo above on the Smithsonian Mag website (I believe) and a little roll-over action identifies some of the people standing by Lincoln. One is the then governor of New Jersey, George Newell (he also started the US Coast Guard, I believe). I now live a scant 2-3 mile from Gov Newell’s Allentown, NJ, house. My daughter goes to Newell Elementary and he’s interred in the cemetery across the street.

LikeLike

I came across this photo of the commemoration the other day.

LikeLike

It’s amazing, isn’t it, how even a small connection with an historical figure can turn them into real people.

And Patrick, that’s incredibly cool…and weirdly moving.

LikeLike