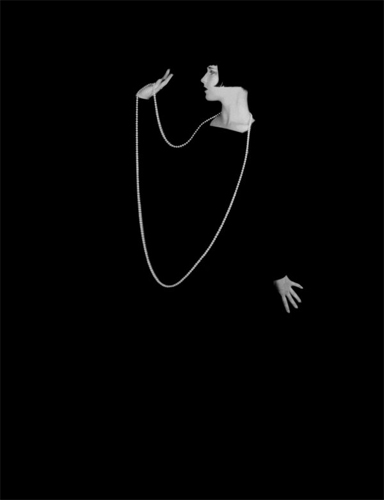

“Nobody burned more bridges than Louise Brooks, or left prettier blazes on two continents.”

It was a pleasant afternoon and I was strolling along the riverwalk, which is a thing I like to do whenever possible. I was thinking about all the stuff I needed to get done, which is a thing I like to avoid thinking about whenever possible. As I approached one of the many bridges that cross the river I noticed a small sketch inked or painted on the side of the abutment.

It clearly wasn’t the usual graffiti. It was a woman’s face, sketched small — not much bigger than my hand. There was something very familiar about the face. It was the hair, mostly — that short angled bob — but even the pose reminded me of something I’d seen somewhere before. I knew that face.

It clearly wasn’t the usual graffiti. It was a woman’s face, sketched small — not much bigger than my hand. There was something very familiar about the face. It was the hair, mostly — that short angled bob — but even the pose reminded me of something I’d seen somewhere before. I knew that face.

I stood there for a time and studied the sketch. There seemed to be a slight Asian quality to her eyes, and I wondered for a bit if it might be a sketch of Anna Mae Wong — the first Chinese-American movie star of the 1920s and 30s. I’d seen a documentary about Wong at some point, and it mentioned her as having gone through a ‘flapper’ period. It might be her.

But no. When I returned home, I cracked open my computer and a quick Google search confirmed it. Whoever it was — if it was intended to be a sketch of an actual person — it wasn’t Anna Mae Wong.

But who was it? I was absolutely certain I’d seen that face somewhere. Maybe I’d come across a photo similar in style while researching a Sunday Salon. Some photographer from the 1920s or 30s, certainly. American? Possibly, but more probably European. A French photographer, perhaps. That hairstyle, though, definitely belonged to the flapper era. Was that a uniquely American Jazz Age phenomenon? Or was the flapper fashion cross-cultural? I’d no idea.

So I tried a Google image search using the keywords flapper bob. It seemed like a long shot…but there she was: first photograph on the first page.

Her name is Louise Brooks, and she wasn’t European. She certainly wasn’t French — at least not by birth. She was born in 1906 in a small town in Kansas, of all places — a town with the improbable name of Cherryvale. She wanted to be a dancer, which was quite an ambition for a girl from Cherryvale (which, at the time she was born, had a population of about 4000 souls — almost double the current population, which tells you something about Cherryvale, Kansas).

Her name is Louise Brooks, and she wasn’t European. She certainly wasn’t French — at least not by birth. She was born in 1906 in a small town in Kansas, of all places — a town with the improbable name of Cherryvale. She wanted to be a dancer, which was quite an ambition for a girl from Cherryvale (which, at the time she was born, had a population of about 4000 souls — almost double the current population, which tells you something about Cherryvale, Kansas).

Louise decided to do what all ambitious Midwestern girls dream of doing: she packed a bag and went to New York City. That was in 1922; Louise was 15 years old.

She was accepted into the Denishawn Dance Company, run by famed choreographers Ruth Saint-Denis and Ted Shawn. By 1923 she was one of the company’s principal dancers. By 1924 she was fired from the company because of her temper. By 1925 she was dancing in London, where she gained some notoriety for being the first woman in England to dance the Charleston on stage. Later that year Louise returned to the U.S. and signed a five year contract with Paramount Studios. She was 19 years old and they told her they wanted to make her a movie star.

And lawdy, they did. They surely did.

She made a number of silent films in the U.S., and her signature hairstyle quickly became adopted by young women all over the country. For the most part Louise played flappers and vamps, roles for which she was perfectly suited since she actually was a flapper and a vamp. Her career at Paramount was tumultuous — she drank too much, she had affairs with men and women (including Marlene Dietrich), she argued with the studio executives, and she alienated directors and producers by ‘reading too many books’ and having too many opinions.

She made a number of silent films in the U.S., and her signature hairstyle quickly became adopted by young women all over the country. For the most part Louise played flappers and vamps, roles for which she was perfectly suited since she actually was a flapper and a vamp. Her career at Paramount was tumultuous — she drank too much, she had affairs with men and women (including Marlene Dietrich), she argued with the studio executives, and she alienated directors and producers by ‘reading too many books’ and having too many opinions.

And once again her fiery temper caused her to be fired. As before, Louise responded to being rejected by going to Europe and becoming a success. In 1929, at the age of 23, she made the film for which she’s best known: Die Büchse der Pandora. Pandora’s Box. Here’s how the movie is described:

The rise and inevitable fall of an amoral but naive young woman whose insouciant eroticism inspires lust and violence in those around her.

Louise played the role of Lulu, the ‘amoral but naive young woman.’ The movie itself is confused and disjointed, but by all accounts Louise personified the role. It lifted her from the status of ‘movie star’ up into the category of ‘movie legend’ and eventually ‘cult figure.’

Her life continued at the same dizzying, passionate pace. She returned to Hollywood, she married millionaires and divorced them, she argued and seduced and drank and danced, she posed in the nude for photographers, she made two more films (one with John Wayne) and then abruptly left the movie business. She moved back to New York and spent herself into bankruptcy. By the time the Great Depression rolled around Louise Brooks was broke but well-dressed. She worked part-time as a salesgirl at Saks Fifth Avenue and part-time as a courtesan, keeping company with the city’s few remaining rich men.

By the 1950s, Louise Brooks was something of a recluse, living in a small New York apartment. Then French film historians rediscovered her and began to revive her films. The critic Henri Langlois declared “There is no Garbo, there is no Dietrich, there is only Louise Brooks.” The French revival sparked interest in the U.S., and caused the film curator of the George Eastman House to track down Louise in New York City. He persuaded her to move to Rochester, NY, where she began to write about her life and acting career. She became something of a film critic herself, and later published an autobiography titled Lulu in Hollywood. When Liza Minnelli was looking for inspiration on which to base her character Sally Bowles in the movie Cabaret, she found it in Louise Brooks. Her life story fueled novels and biographies, it drew the attention of documentary filmmakers, and even became the underlying concept of a popular and influential Italian erotic comic book series — Valentina.

By the 1950s, Louise Brooks was something of a recluse, living in a small New York apartment. Then French film historians rediscovered her and began to revive her films. The critic Henri Langlois declared “There is no Garbo, there is no Dietrich, there is only Louise Brooks.” The French revival sparked interest in the U.S., and caused the film curator of the George Eastman House to track down Louise in New York City. He persuaded her to move to Rochester, NY, where she began to write about her life and acting career. She became something of a film critic herself, and later published an autobiography titled Lulu in Hollywood. When Liza Minnelli was looking for inspiration on which to base her character Sally Bowles in the movie Cabaret, she found it in Louise Brooks. Her life story fueled novels and biographies, it drew the attention of documentary filmmakers, and even became the underlying concept of a popular and influential Italian erotic comic book series — Valentina.

That face went from Cherryvale, Kansas to New York City to London to Hollywood to Germany to Hollywood again and New York City again to Rochester, NY and now it’s on the side of a bridge crossing the Des Moines River, some four hundred miles from Cherryvale. That’s a hell of a journey. It’s a hell of a story. Louise Brooks was a hell of a woman.

That face went from Cherryvale, Kansas to New York City to London to Hollywood to Germany to Hollywood again and New York City again to Rochester, NY and now it’s on the side of a bridge crossing the Des Moines River, some four hundred miles from Cherryvale. That’s a hell of a journey. It’s a hell of a story. Louise Brooks was a hell of a woman.

I saw your link as i was cursing my FB page. I am blown away, I am writing a novel about a girl from Kansas born in 1906! How crazy.

LikeLike

What a great story. Bridges burned, and there is her face anonymously painted small on the side of a bridge. Thanks for the gift of this post, Greg.

LikeLike

Great post Greg. She really lived an interesting life.

LikeLike